West Coast Offense Definition and Pass Protection Terminology

General Introduction to the West Coast Offense

Introduction

If you’re a fan of the NFL, you’ve probably heard the term “West Coast Offense.” You have also probably seen or heard NFL content where a coach or player says an incredibly long play-name that sounds like a language only C-3PO could translate. What do all of those terms mean, and why is “West Coast Offense” said so often? The West Coast Offense, has its roots in the 1960’s and 70’s with the Cleveland Browns and Cincinnati Bengals under legendary coach Paul Brown. When Brown was at Cincinnati, he had a QB coach named Bill Walsh, who would go on to set the gold standard for modern offensive schemes in the NFL with the 49ers in the 1980’s. The West Coast Offense essentially provides a blue print for the modern game we know today. In today’s NFL, you can find the West Coast Offense’s influence within almost every team, and find legacies of the Bill Walsh coaching tree on almost every coaching staff.

West Coast Offense Strategy

Before the West Coast Offense and other pass-first systems, the forward pass was used as a compliment to the running game. In terms of tactics, you would run the ball until the other team’s defense got too strong against the run, or the defensive backs got too close to the line, then you would throw the ball deep, over their heads. If you were to compare this to warfare, think of the running game as your infantry, and the forward pass as planes, tanks and armor support. Tanks were introduced in WWI to support infantry as they charged across no-man’s land, and planes were used for reconnaissance, and to drop bombs over enemy strong-points in the trenches and cities. The West Coast Offense would then equate to the tactic of blitzkrieg developed by the Germans in WWII. Rather than using tanks and planes (the passing game) to support the infantry, attack head-first with your planes first, tanks second, then let the infantry bat clean-up. What the West Coast offense does is exploit the natural holes and weaknesses of a defensive formation or structure with short, fast, precisely timed passes before the defense can flow to the ball, or drop to their coverage areas (these are the planes that initially attack strong-points to soften defenses for the tanks). When executed successfully, the defense would start playing more conservatively, trying to close and prevent those short passes, which would open up both the deep passing game for those gut-punch plays (tanks using speed to overwhelm defenses and get behind enemy lines), then the running game (infantry).

In addition to the innovation of avid dedication to precisely timed short routes, the West Coast Offense was one of the first systems to implement a complex strategy for protecting the QB, while also allowing the offense to use it’s tight-ends and running-backs in the passing game with almost an equal amount participation in the passing game as the wide receivers. If you can distribute the ball in the passing game to all eligible receivers, the defense cannot focus solely on a couple core receivers, giving you more one-on-one situations. Many of these pass protections are the gold-standard for pass protections in the NFL today.

Pass Protection Terminology

The West Coast Offense Walsh used primarily relies on numbers to call pass protections. The terminology you will see in this article are being borrowed from this 356 page, 1985 49ers Playbook that can be found on Google. This article does NOT cover all the pass pro terminology in this playbook, but it covers all the basics. In this playbook, there are two primary types of protection. 1. Pocket/Cup Protection, and 2. Slide Protection. In both protections, the default rule for all running-backs and tight-ends is to execute an assignment called “check-release,” which means they are assigned to a defender (or two), and if that defender blitzes (blitz is called “dog” in the playbook), they block them. If the defender does not blitz, they “release” into a route to receive a pass. They release, because that defender they’re assigned to is not a threat to sack the quarterback, so rather than wasting a blocker, they want those players to get involved as receivers incase the primary receivers on a play are not open. For quarterbacks, these backs and tight-ends often serve “check-down” roles, meaning if the primary receivers in the progression aren’t open, the QB finds these players for an easy release valve rather than holding onto the ball and risking a sack.

Pocket and Slide Protection

Pocket/Cup Protection: Your center and guards protect the center-three defenders of the defense. Tackles identify and block the defensive ends. Your backs and TE’s protect the OLB’s. Backs protect inside-out, meaning they block an inside rush threat first, then work outside if there is no inside threat.

Slide Protection: This one can get a little complicated, so take your time. In slide protection, you call a side to set the protection to (left/right, strong-side/weak-side, whatever).

If you call the protection to the right, that means the offensive linemen on that side will BOB protect. BOB means “big on big/back on backer.” That means offensive linemen block the nearest defensive lineman, and any backs in the formation block linebackers (or “linebacker-types”) to that side. Default rules tell backs in protection if their defenders do not blitz (“no dog”), they release.

To the left side (or weak-side/back-side), the offensive line will slide. The slide begins at the first offensive lineman to the strong-side/play-side that does not have a defender in their play-side gap. In this case, the protection is set to the right, so the first offensive lineman to the right of the center with no defender in the gap to their right is the first offensive lineman in the slide.

Linemen in the slide protect the gaps to their back-side/weak-side (the left side in this example), and are also responsible for the Will linebacker.

I will write another article that does a deep dive into slide protection, because it’s arguably the most popular and favored pass protection in football today.

Numbering System

In the classic West Coast Offense, they use a numbering system to call their series (plays that have a common set of rules), and specific plays. Since this article is about pass protection, we will cover what in Walsh’s system are the 20’s, 50’s, 70’s, 80’s, and a BASIC introduction to 2/3 Jet protection.

Most protections have two numbers. The first number indicates the type of backfield action/movement the backs will take, and the basic type of protection. The first number also sets the default rules for all numbers in that series. The second number indicates the specific type of protection/modification within that series. Remember pocket and slide protection that was mentioned above. Even numbers mean the TE (strong-side) is to the right. Odd numbers mean the TE is to the left. If you look at the playbook link, the best description of the pass protections begins on page 251.

Some other terms you need to know before going into the numbered series:

Scat: Scat means a back “free releases” (meaning they run a route right off the snap, and have no blocking responsibility. In terms of protection, “scat” indicates that the side a back free releases to calls for the offensive guard, or uncovered lineman to that side to double-read the the linebackers to that side.

Double read: An offensive player is assigned two defenders to block. Usually, they work inside-out, blocking the inner-most defender first. If that defender does not blitz (“no dog”), they then look to block the outside defender. If both blitz, they block the inside defender.

Hot: When a back or tight-end is assigned a “hot” responsibility, it means if their assigned defender blitzes, they bypass them and look for a quick pass from the QB.

Rip(Right)/Liz(Left): The back on the side called “check releases” on the inside linebacker to that side. They release if the ILB does not blitz. If the ILB blitzes, they sneak a peak at the outside linebacker (OLB) to their side. If the OLB does not blitz, the back releases. The back away from the call side is coming over to that side to get the blitzing ILB. If the OLB blitzes, the back then becomes the “hot” receiver, and replaces the OLB’s position to get open.

Stay means a back or tight-end does not release (they block for the whole play). Slow means a back or tight-end releases only if their assigned linebacker (or linebackers) does not blitz. Max means all backs and tight-ends release, and the protection always becomes “pocket” protection (so if slide was called, “max” turns it into pocket protection).

Swap: When there are two backs in the backfield, they essentially cross each other off the snap.

100: Any play with a “1” in front of it (making it a triple digit play starting with 100) means the QB takes a 3-step drop. This makes it a “quick pass,” where the line and backs will block aggressively and hold the defense at the line of scrimmage.

200: The QB takes a 5-step drop, and the protection becomes slide protection (in other version of the WCO, you see 200/300 as both slide protection, and a 3-step drop).

If you have an I-formation, the “strong back” is the closest back to the TE, so it’s the fullback. The deep back/tailback is the “weak back.” In any 2-back formation, the back closest to the TE is the “strong” back. Walsh’s terminology talks in terms of halfbacks and fullbacks, but I am using “weak” and “strong” back so it’s more fluid across systems and more modern formations.

20’s: Split-Flow/Divide Protection

Split flow protection is a pocket protection, where both backs move opposite of each other off the snap (if you have a back to the left and right of the QB, the left back moves left, and the right back moves right). All backs (so two backs) check-release, and the TE free releases if there is one. Unless a specific protection says otherwise, players not mentioned use the rules described above.

20/21, 22/23: Basic split-flow rules as described above.

24/25: The back to the weak-side (away from the TE) scats (free releases) to their side into a route. The guard or uncovered lineman to the weak-side must now “scat” protect to that side, meaning they double read the ILB to OLB on the weak-side.

26/27: The back to the strong-side scats and the strong guard/uncovered lineman scat protects.

28/29: Max protect

228/229: Slide protection to the weak-side (away from TE). Weak back free releases. Strong back only has ILB (or Mike) to their side, and check releases off them. TE check-releases off the OLB to their side.

50’s: Split-Flow/Divide with Rip/Liz Protection

Also a pocket and two-back protection series. This is almost the exact same as the 20’s, but the Rip/Liz rules are now applied. TE free releases by default.

50/51, 52/53: Backs split-flow using Rip/Liz rules (back closer to the right Rips, back closer to the left Liz’s.

54/55: Rip/Liz only applies to the weak-side (so 54 is TE to the right, meaning weak side is left, so Liz is ran. 55 is TE left, so we Rip). The weak back and guard double read ILB to OLB to the weak side, and the back check-releases vs. no blitz.

56/57: Rip/Liz to the strong-side only. Strong back and guard double read the ILB (Mike) and the back check-releases.

58/59: Max protect

70’s: Weak Flow Protection

Weak flow is another pocket protection series normally ran from two-back sets. However, since both backs are going away from the TE off the snap (weak flow), the TE is now check-releasing by default on all 70’s plays, primarily to block the OLB to their side. The weak-side back free releases, while the strong back check-releases to the weak-side.

70/71, 72/73: Default weak-flow rules

74/75: Both backs free release to the backside, and the O-line scat protects to the weak-side (guard/uncovered lineman double reads ILB to OLB).

76/77: Weak flow with scat protection to the strong-side: The TE is now free releasing. The TE is not blocking at all, and both backs go weak, so there are only lineman blocking to the strong-side, requiring the scat protection.

78/79: Both backs flow weak, and check release. The weak-side back has OLB, and the strong-side back has ILB/extra/garbage.

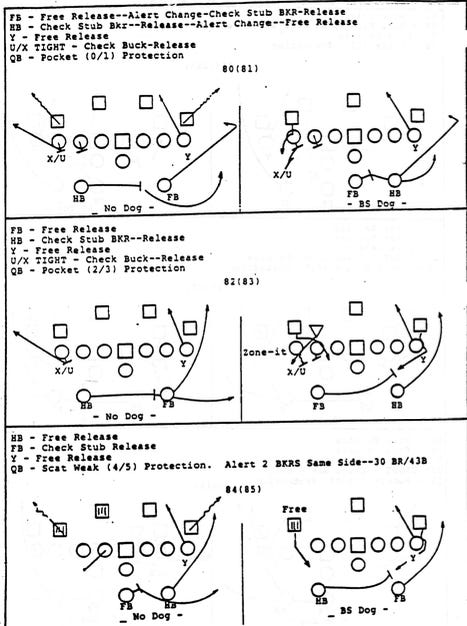

80’s: Strong Flow Protection

Strong flow is the opposite of weak flow (another two-back pocket-style protection). The TE free releases by default, because now both backs are coming to their side. The strong-side back free releases, and the weak-side back check-releases. These series also require a 2nd TE to be in the game to the weak-side (so there’s a TE on both sides, or the TE is actually to the “weak side,” or away from the call side). This is necessary, because both backs are going strong-side, giving the O-line no potential help to the weak-side. The TE to the “weak-side” check-releases.

80/81, 82/83: Default 80’s rules.

84/85: Scat protection weak (TE to that side free releases).

284/285: Slide to the weak-side (284 means slide is left, backs right). The weak-back coming to the strong-side double-reads the ILB to strong OLB (Mike to Sam).

86/87: Scat protection strong-side with both backs free releasing.

88/89: Requires a TE on each side. Backs free release and both TE’s block the OLB/OLB-area to their side.

Below is an image of the drop-back pocket-protection summary from the playbook:

2/3 Jet Protection: Slide Protection

Popularly known today as “half-slide protection” all 2/3-Jet plays are slide protection with one back (always a 6-man protection). This means four receivers are automatically in route. It can be ran from three, two, or one-back formations. It’s the same slide protection described earlier, and as I said before, I’ll be doing a more in-depth article on this protection in the future, because it’s so popular and favored today.

200/300 Jet is the same protection, but now the QB is taking a 3-step drop, and the line is blocking aggressively.

You can hear QB’s in the NFL today calling this exact protection, with these exact terms. It’s so popular that every offense and defense knows it to a point where offenses will just call it what it is, because it can’t really take defenses by surprise anymore.

Play Action Series

Play action means the offense will fake a run, then throw a pass. This is to get the defense to bite, or jump forward, leaving space open behind them for receivers to run. In the playbook this article is based off of, Walsh uses three digits. The first digit indicates the type of play action protection, and the 2nd and 3rd numbers indicate the run action. So “416” means they’re faking a “16” run play and using 400 protection.

300: Remember, this book does not use “300” like modern WCO terminology uses it. 300 is an AGGRESSIVE slide protection (so slide protection with the O-line and backs attacking and holding their blocks at the line of scrimmage (LOS). On 300, the slide goes away from the call. If the call is “314” the slide is going to the left, and “315” means the slide is going to the right.

400: Slide protection away from the call with a cross-action/misdirection backfield or run fake.

500: Gap protection: The O-line steps to the back-side/away from the call and protects the gap. “598” means they fake a 98 run and the line protects the gap to their backside (left), and “599” means they fake a 99 run and the line protects the gap to their backside (right).

“Run Passes:” If a run is called with “pass” tagged onto it, like “16 power pass,” or 19 BOB pass,” the offense executes the running play, but blockers do not go downfield so that a pass can be thrown. These are great for setting up boot passes to get the defense going one way, so the QB has room to run the other way.

Run Terminology

Here’s a little bonus. Run-game terminology is much more simple. Two digits. First digit indicates who’s carrying the ball, and the second number is the hole, or point of attack the ball carrier takes it to. Walsh used a traditional hole-numbering system: Evens right, odds left. Low-inside, high-outside. 0/1: Off the center’s left/right butt-cheek. 2/3: A-gap (between center and guard), 4/5: B-gap (between guard and tackle), 6/7: C-gap (between tackle and TE), 8/9: Outside

10’s: Runs to an offset back at a depth of 4-5 yards coming across the formation/behind the QB (so like a fullback in an offset-I, or a halfback next to the fullback).

30’s: Trap and toss plays from an offset back at 4-5 yards. The back typically does not come across the formation, or at least behind the QB.

40’s: Draw plays

60’s: Runs to a back behind the QB at a depth of 4-5 yards

90’s: Runs to a back at 6-7 yards behind the QB (so a tailback).

Alternate Play Action Protection Terminology

For this section, I’m going outside the playbook a little bit, and drawing from some more modern nomenclature. The West Coast Offense has a simplified play action pass protection system to easily incorporate run fakes on almost any play. This default/watered down play action system is a slide protection (so half-slide in modern terms, just like 2/3 Jet). When there are two backs in the backfield, default rules have both backs going to the same side. The back faking with the QB attacks the inside A-gap (between center and guard) and check releases reading Mike to Sam linebacker, and the non-faking back attacks the B-gap and check-releases reading Sam to the next outside threat. When the backs release, the faking back who is more inside will break to the inside, and the back protecting outside will release outside. On all play actions, if the faking back sees their primary blocking assignment blitz, they come off the fake immediately to make the block. The QB should see/feel the back’s movement on this, telling them to quickly drop back and look to throw to the hot route, or get into the progression.

H2/H3: “H” stands for halfback (so think your primary running-back. “2” means fake action to the right, and “3” means fake action to the left. Therefore that back attacks A-gap, and the second back attacks B-gap.

F2/F3: AKA “Fox 2/Fox 3” if you want to sound cool, is the same as H2/H3, but now the fullback or other back is faking and taking the A-gap, while the halfback/tailback goes B-gap.

Fire 2/Fire 3: I got this term from this page, which alters the terminology slightly (so ignore this sheet for this article, except for “fire 2/fire 3”). It’s a 6-man version of this play action protection where you fake to the tailback/halfback, and the 2nd back and TE are free releasing. Both can be a hot receiver. The idea is to anticipate a defensive blitz, get the quick fake to hesitate LB’s and the secondary, then quickly get the ball out to the TE or 2nd back.

Empty Protection

Empty protection (no backs or TE’s in protection; just the five linemen) could be done with either pocket or slide protection. When you run pocket protection, the uncovered lineman to each side double-reads ILB to OLB to that side. In slide protection, you BOB to the call side, and slide to the other side, with the uncovered lineman on the slide side checking the Will LB first (because in slide, the sliding linemen are responsible for the Will LB), then look for the OLB to that side. If no one comes, the lineman assists to their side, or picks up any garbage they happen to see coming through.

Summary

The West Coast Offense provided a blue-print for the modern offensive game in the NFL, primary with its flexibility of various pass protections. Using a numbering system and relying on mostly pocket and slide (half-slide) protections, Bill Walsh and his coaching staffs compiled a system that would allow them to flood the field with receivers from all sorts of different angles and personnel groupings, while also giving them multiple ways to protect the QB from the wide range of defensive schemes and blitzes. If you’re still confused about the orientation of the numbering system, remember this: They are oriented based on the location of the TE. The side the TE is on is the strong-side, and the side away from that is the weak-side. If the number called is even, it means the TE is to the right. If the number called is odd, it means the TE is to the left.

Thank you so much for reading, and I hope to write more articles in the near future. If you have any requests you would like to make, please reach out and comment below. I’m always open to feedback as well, so if there is something you feel is incorrect or should be described more thoroughly, please drop a comment!

Still confused about the play numbers. In your diagram, you show 3 Jet as being the play call to the left, but the tight end is to the right! In your summary, you say that an odd number means that the TE is on the left!