Introduction

When you hear the words “triple option,” what comes to your mind? Is it the glory days of the Wishbone in the 1970’s and 80’s, or do you think of the military academies? If you’re thinking of one or the other, you’re correct. Now, what if you were told that many of the college offenses you see on TV today are also running the triple option? If you’re thinking of the military academies or that classic under-center triple option, you could easily argue that these programs are not doing that, and you would be correct. However, it is also incorrect. This article is going to further define what a “triple option” is, and some of the more common styles or “families” of executing them.

WHAT IS A TRIPLE OPTION?

An “option” play in most football terminology is a play designed to be a run, where whoever takes the snap is making a post-read decision on giving the ball to one of two players. In most cases, one of those two players is the person taking the snap. Often, these ball transfers are in the form of a hand-off (also called a mesh), or a pitch/lateral. The ball carrier makes this decision by reading a specific defender and the actions they make. If the defender attacks one option, they choose the other option.

A triple option is any play that has a designed run called, but instead of two options being made by the player taking the snap, there are three. In order to create a triple option, the person making the decision must now read two defenders. When the snap is taken, they make the first read, then after doing so, they move on to the second read. Often times, the options are to give the ball to one player, keep it themselves, or get the ball to the third player.

If we look at option plays with this kind of description, notice how there are no rules or limits as to how the ball is distributed. It can be a handoff, a lateral or pitch, or a pass, or if the person making the decision is keeping the ball, none of the above.

To summarize a “triple option,” it is any play that features a designed run, with the intention of making a post-snap decision as to who gets the ball between three players. Traditionally, the defenders that are read are also left unblocked. If this is the case, there are always at least two intentionally unblocked defenders; one for the decision between options one and two, and the other for the decision between options two and three.

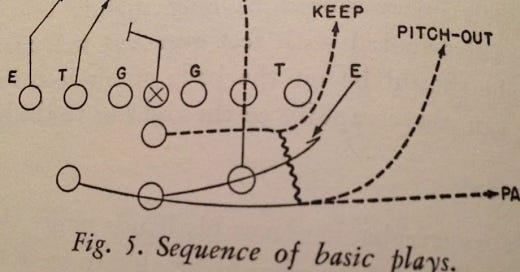

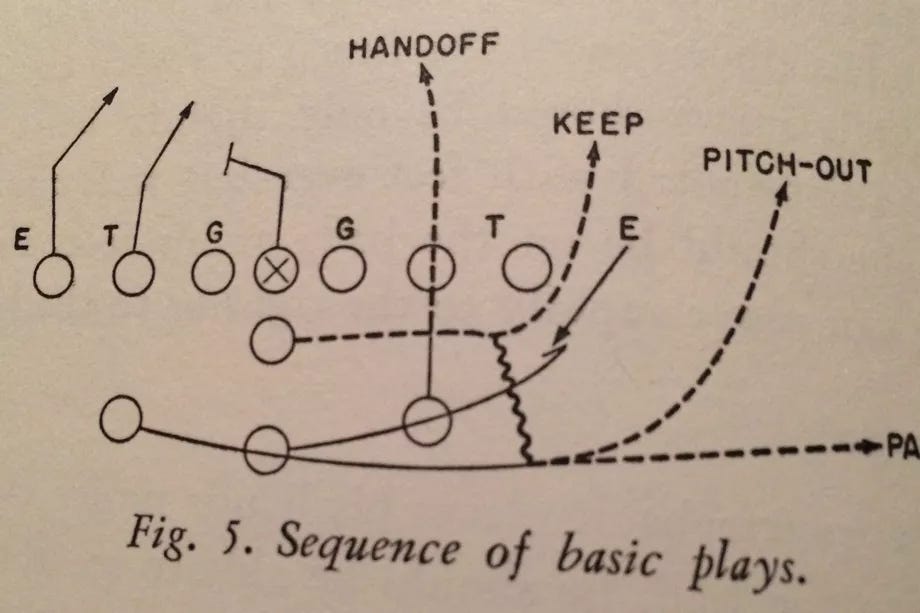

ADVENT OF OPTION FOOTBALL

Most say option football began with the “Split-T” offense that was very popular in the 1940’s and 50’s. Developed by the Missouri Tigers at the start of the 40’s, the offense spread throughout football, and became the offense of infamous Oklahoma coach Bud Wilkinson. The Split-T was an offense operating out of a T backfield, where the line splits were very wide, usually around three feet. The “split” represented the wide line splits, and in later versions, the feature of moving one of the two tight-ends into a split-end alignment. The base play of this offense features a dive component, where the QB runs straight down the line of scrimmage to mesh with a diving halfback. The fullback behind the QB would then lead block around the end, with the trailing halfback following the fullback. The “called” plays out of this action were halfback dive, QB keep, and halfback pitch. As the offense evolved, the QB keep component began to add the addition of a read, where the QB would either keep the ball, or pitch it to the trailing halfback. With this series, you have the foundational movements of the classic triple option: A dive, a QB keep, and a pitch phase.

Following are some YouTube links with more insight on the Split-T offense:

The Veer…The Veer and The Wishbone

Developed in the 1960’s, the Veer and Wishbone offenses feature what most think of when you hear the word “triple option.” The Veer and the Wishbone’s core play was…the veer. When you hear “the veer” as an offense, it usually means the split-back veer, or “Houston Veer.” The Veer offense differs from the wishbone in that it operated from a split-back backfield, using more pro-style formations, featuring a tight-end, split-end, and flanker.

The Wishbone sought to find a more balanced approach. Designate a larger, more bruising back to execute all the dives to the left and right, while mirroring the two halfbacks, that way the defense could not determine which side of the formation the offense was more likely to run to.

The veer play itself (also known as inside veer) is a simple scheme: Double team/block down inside the hole, then everyone else to the backside base blocks. This leaves the DE, and the next defender outside of the DE unblocked. The three options are the dive back attacking the guard’s butt to the B-gap, the QB keeping off tackle, and the pitch back trailing behind. The QB’s first read was the DE. If the DE attacks the dive, the QB pulls. If the DE sits or runs up-field or at the QB, the QB hands off. When the QB keeps the ball, they move on to the next unblocked defender. If that defender attacks the QB, the QB pitches it to the trailing halfback. If the defender stays wide or attacks the pitch back, the QB keeps and runs up-field.

The common rule of blocking on the inside veer is that the first defensive player on (over) or outside of the play-side tackle is the dive read. In most defenses, this is a defensive end, but now always.

Both offenses also developed secondary veer plays as well, most notably the outside veer, considered by many as the most difficult veer play to stop. The outside veer is pretty similar to the Split-T option play. The dive back attacks the C-gap or outside the tackle, rather than the guard or B-gap. The QB executes the same reads and the pitch back runs the same track. All that really changes on the O-line is that instead of leaving alone the first defender on or outside the play-side tackle, they now leave the first defender on or outside the tight-end unblocked. Sometimes this is a defensive end. Sometimes this is an outside linebacker.

A third type of veer play is the midline. This was probably the latest of the three veer-type plays to develop, and is definitely the most nuanced. Same rules as veer: block down inside the hole, leave the first defender on or outside the hole unblocked. With the midline, the dive back now dives straight forward at the center’s…midline. The QB backs up, out of the back’s path to make the mesh/read. The read defender is now the first defender on or outside the play-side guard. The midline was primarily used as a double option just between the QB and dive back, but as the play gained popularity with the later flexbone teams, a triple option version became feasible as well.

Fisher DeBerry’s Flexbone

Into the 80’s, Air Force head coach Fisher DeBerry was looking for a way to make his Wishbone offense more “flexible.” One of the major setbacks of the wishbone is that there are only two players, the two ends, who could be immediate deep passing threats. To increase the passing threats to the defense, he “flexed” the bone and put the halfbacks outside of the tackles, toward the line of scrimmage. This formation, paired with the wishbone system, became known as the flexbone.

Today, Air Force still runs DeBerry’s system, but they have evolved greatly into a multiple offense, running triple option plays from just about every formation imaginable.

Paul Johnson’s Flexbone

Developed at Hawaii in the early 1990’s, Paul Johnson’s flexbone option offense is what most fans today think of in terms of “triple option” teams. Army and Navy both currently run Paul Johnson’s system, and Johnson also ran it at Georgia Tech. This is also the offense that Paul Johnson used to build Georgia Southern into a I-AA powerhouse in the late 90’s, and ever since then, Georgia Southern has gone back and forth between this system with changes in coaching staffs.

Paul Johnson’s flexbone evolved differently than DeBerry’s at Air Force. When this offense formed at Hawaii, the formation was already there, but Hawaii was running the Run ‘n’ Shoot. The Run ‘n’ Shoot is a very pass heavy, downfield, four wide receiver offense that developed in the 1960’s, and for decades, was a major offensive threat in college and the NFL. At Hawaii however, when Johnson was an assistant, they were looking to make their running game more effective. They started by innovating their own toss sweep series called the rocket toss, then later borrowed ideas from Fisher DeBerry at Air Force, including the inside veer and midline veer. As time passed, Hawaii’s Run ‘n’ Shoot became less shoot, and more run (with the help of an excellent option quarterback named Ken Niumatalolo), eventually turning into the offense Paul Johnson brought with him to Georgia Southern, then Navy, then Georgia Tech.

If you want to see the Run ‘n’ Shoot in its most original form today, you want to watch Army and Navy!

The “Ski-Gun”

The Ski-gun is a lesser known version of the flexbone option offense, but still has the inside veer at its core. Developed at Muskegon High School (MI), pronounced “Muh-ski-gun,” head coach Tony Annesse made his own adaptations to Paul Johnson’s offense, leading Muskegon to multiple state titles. They proudly claimed the name of this variation, the “ski-gun.”

The Ski-gun is an “even more spread” version of the wishbone/flexbone system. The slot-backs are moved out wider, into more twin/slot receiver looks, with the QB in a VERY short shotgun snap, usually about 2.5 yards, three at most. The slot backs would also be even in depth with the QB. That way if they went in motion, defenses couldn’t tell if they were going behind the QB to be a pitch back, or in front of the QB to run a jet sweep.

Today, Tony Annesse is the head coach at Ferris State University (MI), and he has since adapted his offense to more modern concepts that are popular in college football, like RPO’s, which this article will get to shortly. The core of his “ski-gun” is still there, and it has grown a small and committed cult following among some high school coaches.

I-Option Offense

Arguable the most devastating offensive attack ever in college football were the Nebraska Cornhusker teams under Tom Osbourne in the 1990’s. While these teams relied on more double options, like midline, freeze, dive, belly, down, and lead option, triple options existed as well. In addition, they had a very potent power running attack with toss sweeps, ISO’s and power plays. The blocking they used for the triple option was veer, just like the veer and bone offenses, but now they could always have their stud tailback as the pitch back.

Zone Read Triple Options

Yes! The zone read can be a triple option play! Remember Oregon with Chip Kelly? Or Georgia Southern in recent years? Or Bob Davie at New Mexico? They’re zone read systems that rely heavily on triple options.

Think of your typical zone read: The O-line blocks inside or outside zone. The QB and RB mesh, and the QB reads the backside defensive end for give or keep. Now, leave the next defender outside the DE unblocked. Bring a back or receiver into the backfield via formation call or motion, and have the QB read that second unblocked defender. Either keep, or pitch to that extra receiver or back.

Here’s what’s really amazing about running triple option from the zone read…it works just like inside veer. Let’s say you call an inside veer to the right. The linemen on the play side are going to block down (to their left). The dive back is going to charge hard forward while the QB opens, facing the right, reading the play-side DE.

Now picture a zone read to the left. The linemen on zone plays always step play-side to the left (the linemen on the backside of zone read step to their left). The dive back plunges forward, while the QB opens, facing to the right, reading the backside DE.

THEY’RE THE SAME PLAY! Well, almost. There are two major differences. The first is the dive-back’s assignment. On veer, the hole or dive path is fixed, meaning the back dives forward to the B-gap, then stays on that “veer” track, angling off the wall of down blocks. On zone, the back is reading the blocks, and is making a read as to which direction to take the ball. The second difference is the blocking technique. Veer schemes typically have linemen with their weight far forward, and lunging out, almost on all fours to block the defense, using mostly shoulders to block or pin defenders. Zone principles teach a more balanced stance, and using hands and leverage to steer defenders in a particular direction.

Some systemic differences across teams. At Oregon, with Chip Kelly, their zone read offense relied on spread-heavy sets, creating lots of natural running lanes, and maintaining a constant four-vertical passing threat to a defense.

At New Mexico with Bob Davie, and at Georgia Southern (After Paul Johnson went to Navy), they maintained the full house/four-back offensive style the flexbone and wishbone. This style was popularized by a coach named Tony Demeo when he coached at various sub-FBS/I-A programs. Think of it as a marriage between the split-back veer and the zone read. The base backfield has two backs to either side of the QB. One would run inside zone one way, while the other was the pitch back crossing over. When zone left is called, the option is to the right, and vice versa. Along with this split back approach, these teams would also at times use a tight-end or fullback in an H-back, or “sniffer” back alignment, which is in front of the QB offset to the left or right. This player would serve as an extra lead blocker on either the zone play, or could release outside to lead block for the QB or pitch back on the edge.

As spread formations became the hip trend, and as the Air Raid began to make its rounds in college football, teams began looking for ways to apply triple option football, especially the zone-read triple option to the passing game.

Along with zone read from spread sets, teams have also used power and veer schemes to run shovel options as well. On a shovel triple option, the back that receivers the forward shovel pass is the first read. The pitch back is the third read.

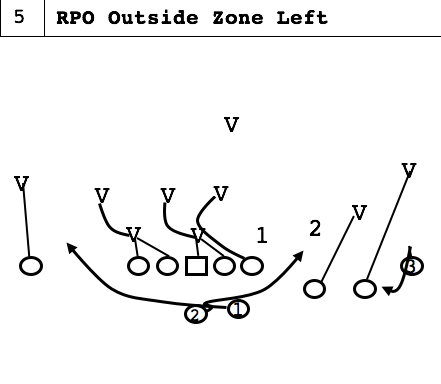

RPO Schemes

Here is the offense that everyone in big time college football seems to be running right now. 11 personnel (1 back, 1 TE, 3 WRs), with the TE playing as the “H” or “Hybrid” back position. You see teams running a steady dose and combination of inside zone, outside zone, power, and counter. At the same time, you’re seeing what looks like these running plays actually turning into passing plays. What we are seeing is an application of option and triple option football to a more diverse running and passing game.

Run-Pass Options are what this article will focus on, since they emulate the triple option philosophy most closely. We started seeing these schemes develop in the 2000’s with some of the first zone-read heavy coaches like Rich Rodriquez, Brian Kelly, and Chip Kelly. Think of your typical triple option: You read the first defender on or outside the tackle for hand off or QB keep. Then you read the next defender outside for QB keep or pitch. Now, rather than having a pitch back coming from behind the QB, put that pitch back as a wide receiver out by the sidelines, to the outside of that second unblocked defender. If that defender attacks the QB, the QB throws the ball to that receiver, rather than pitching it. You now have what is essentially a run-pass option. With run-pass options, you have an almost limitless combination of triple option read styles.

One style is like the one just described: Read the DE, then the next defender out for hand off, QB run, or pass. Another style is to block the defensive end according to a called run play, like power (fullback/H-back kicks out the DE). The QB then reads the next defender out, and can either give or keep, or give or throw. You can turn this into a triple option by leaving the next defender outside that first one unblocked. Now you’re leaving the third defender outside (or behind) of the DE unblocked. Now the QB can give, keep and run or keep and throw, with the third option being another pass option.

Summary

We mostly know the term “triple option” as the famous inside veer play that dominated college football in the 70’s and 80’s, then today with the military academies. The fact is triple options are so much more than that. Today, you can run triple options with a dive, keep, and pitch phase, or a dive, keep and pass, or a dive, pass and pass, or any other combination of the three. There are many flavors of triple option, and you can find these various types throughout all of football, from youth levels, to the NFL. To have a triple option play, regardless of the style of offense, you need these components:

A called run play/scheme for the offensive line and a running-back.

Two unblocked defenders that are read by the QB, or a designated player, who will then determine if the ball will be handed off on the called run (option 1) or redistributed to one of two other players (options 2 and 3). One of those other players can be the person making the read (QB keep).

If you can identify these two components, you have yourself a triple option play.